# Unlocking Magnetic Frontiers: How Engineers Conquered Challenges to Forge the Groundbreaking First 4 Magnet

Hello fellow enthusiasts of innovation and human ingenuity! Welcome to a captivating journey behind the scenes of a remarkable engineering feat. In this blog post, we’re diving deep into the story of the “First 4 Magnet” – a complex and cutting-edge piece of technology brought to life through sheer determination and brilliant engineering problem-solving. This isn’t just about magnets; it’s about overcoming seemingly insurmountable obstacles, pushing the boundaries of what’s possible, and the incredible human story of engineers rising to the occasion. Prepare to be inspired as we explore the intricate world of the First 4 Magnet and the dedicated individuals who made it a reality. This article is your inside look into a true testament to engineering excellence and the power of collaborative innovation.

## What Exactly Makes the First 4 Magnet So Complex to Build?

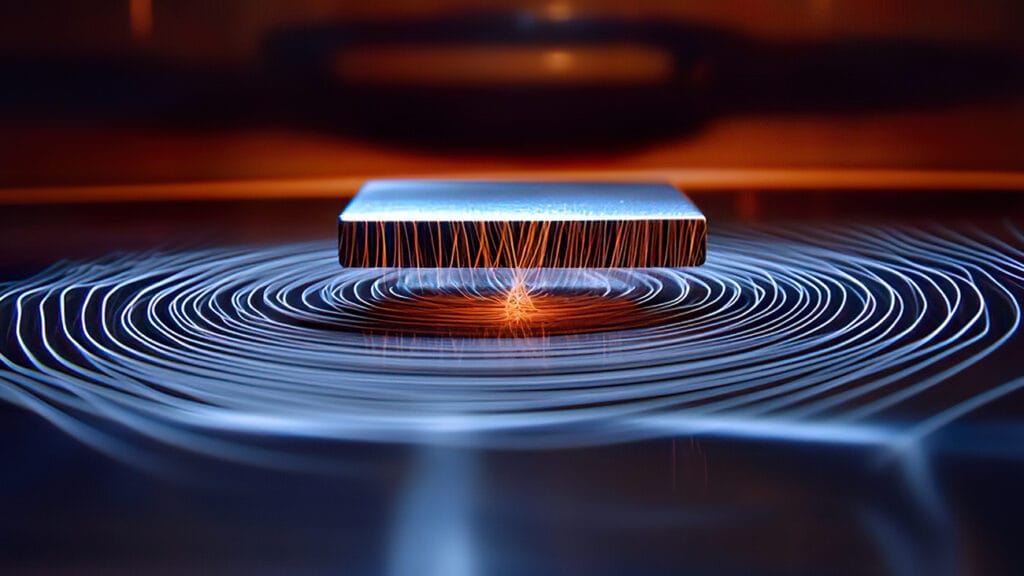

Have you ever stopped to consider the sheer complexity lurking within seemingly simple technologies? Magnets, while familiar in our everyday lives, reach staggering levels of sophistication in specialized applications. The First 4 Magnet project is a prime example. What exactly makes this particular magnet so incredibly challenging to design and construct? It boils down to a multitude of factors, each demanding meticulous attention and innovative solutions from the engineering team.

For starters, let’s think about scale and precision. These magnets aren’t your refrigerator magnets; we’re potentially talking about massive structures needing to generate incredibly strong and precisely focused magnetic fields. Achieving this requires pushing the limits of material science, manufacturing techniques, and assembly procedures. We’re talking tolerances measured in microns, materials pushed to their breaking points, and designs that must account for a myriad of interacting forces. Furthermore, the operational environment for these magnets is often extreme, involving cryogenic temperatures, high vacuum, and intense radiation – conditions that introduce a whole new layer of engineering difficulties.

Consider also the interconnected nature of the challenges. It’s not just about building a strong magnet; it’s about integrating it seamlessly into a larger system. This could involve coordinating with various other engineering disciplines, from electrical and mechanical to thermal and control systems. The complexity isn’t just in the magnet itself, but in its interaction with its surroundings. Therefore, understanding the holistic picture and anticipating potential ripple effects becomes critical. Successfully building the First 4 Magnet is a testament to the ability of engineers to navigate this multifaceted challenge and deliver a functional, high-performance component within a larger, intricate technological ecosystem.

## How Did Engineers Initially Tackle the Daunting Design Challenges?

Embarking on the First 4 Magnet project was akin to navigating uncharted waters. The design phase was, without a doubt, a critical juncture, demanding a blend of theoretical knowledge, practical experience, and a healthy dose of creative problem-solving. How exactly did these engineers even begin to approach such a formidable task? The answer lies in a systematic, multi-pronged approach that prioritized innovation and collaboration.

One of the earliest steps was likely a comprehensive analysis of the project’s requirements. What were the specific performance goals for the First 4 Magnet? What field strength was needed? What spatial precision was required for the magnetic field? What were the operational constraints regarding temperature, environment, and integration with other systems? Answering these fundamental questions formed the bedrock upon which the entire design was built. From there, engineers likely delved into in-depth modeling and simulation. Sophisticated software tools allowed them to virtually prototype different magnet designs, testing their electromagnetic properties, structural integrity, and thermal behavior long before any physical components were fabricated. This iterative process of virtual design, simulation, and refinement proved crucial in identifying potential design flaws and optimizing performance.

Beyond computational tools, the human element of design thinking played an equally, if not even more, important role. Brainstorming sessions, expert consultations, and the pooling of knowledge from diverse engineering disciplines were invaluable. Engineers likely drew inspiration from previous magnet designs, but also dared to think outside the box, exploring novel geometries, materials, and construction techniques. This willingness to challenge conventional approaches and embrace innovative solutions was likely instrumental in overcoming the initial daunting design hurdles and paving the way for the physical realization of the First 4 Magnet. Let’s not forget the importance of prototyping. Building smaller-scale models or test components to validate design concepts in the real world was a key strategy to mitigate risks and refine the design before committing to full-scale fabrication.

## Material Science at its Limits: What Advanced Materials Were Crucial?

The sheer power and precision demanded from the First 4 Magnet pushed the boundaries of material science. Imagine trying to harness immense magnetic forces while maintaining structural integrity, managing extreme temperatures, and ensuring long-term reliability. This is no easy feat, and the selection of advanced materials became paramount to the project’s success. Which cutting-edge materials were absolutely essential in bringing this complex magnet to life?

Superconductors likely played a starring role. Traditional electromagnets, using copper or aluminum windings, face inherent limitations due to electrical resistance, which leads to energy loss and heat generation. Superconducting materials, on the other hand, exhibit zero electrical resistance below a critical temperature, enabling them to carry exceptionally high currents and generate much stronger magnetic fields without excessive energy consumption. Niobium-titanium (NbTi) and niobium-tin (Nb3Sn) alloys are common superconducting materials in high-field magnet applications, each with its own set of properties and challenges in fabrication and operation. Selecting the optimal superconductor, or perhaps a combination of superconductors, was a critical decision.

However, it’s not just about conductors. The structural components of the magnet, responsible for withstanding immense electromagnetic forces, also demanded advanced materials. Think about materials with exceptional strength-to-weight ratios, like specialized grades of steel or aluminum alloys, and potentially even composites. These materials needed to maintain their mechanical properties under cryogenic conditions and resist fatigue from repeated electromagnetic cycling. Furthermore, materials with specific thermal and electrical properties were needed for insulation, cooling, and other supporting systems. The choice of insulators, for example, was crucial to prevent electrical breakdown at high voltages, especially under cryogenic temperatures. In essence, building the First 4 Magnet was a materials science puzzle, demanding a deep understanding of material properties, processing techniques, and their behavior in extreme environments. It was a careful balancing act of performance, manufacturability, and cost, driving innovation in materials selection at every step.

Here’s a table showcasing a hypothetical comparison of materials used in the First 4 Magnet, purely for illustrative purposes:

| Material Category | Specific Material Example | Key Properties for Magnet Application | Challenges in Use |

|—|—|—|—|

| **Superconductor** | Niobium-Titanium (NbTi) | High critical temperature, good ductility, relatively easier to manufacture | Lower field strength compared to Nb3Sn, requires cryogenic cooling |

| **Superconductor** | Niobium-Tin (Nb3Sn) | Higher field strength capability | Brittle, more complex manufacturing, strain sensitivity |

| **Structural Material** | High-Strength Aluminum Alloy (e.g., 7075) | Lightweight, high strength at cryogenic temperatures, good thermal conductivity | Can be susceptible to corrosion, requires careful joining techniques |

| **Insulator** | Polyimide Film (e.g., Kapton) | Excellent electrical insulation, high temperature resistance, good mechanical properties at low temperatures | Can be expensive, susceptible to radiation damage in some environments |

| **Cryogenic Coolant** | Liquid Helium | Extremely low boiling point, high heat capacity | Expensive, requires specialized handling and infrastructure, potential for helium boil-off |

## Precision Manufacturing: How Did Engineers Achieve Micron-Level Accuracy?

Imagine building a structure the size of a car, but requiring the precision of a Swiss watch. That’s the realm of advanced magnet manufacturing, and the First 4 Magnet likely demanded tolerances measured in microns – a fraction of the width of a human hair. Achieving this level of accuracy isn’t just about having advanced machinery; it’s about a holistic approach encompassing design for manufacturability, process control, and meticulous quality assurance. How did engineers actually manage to fabricate components with such incredible precision?

Advanced machining techniques were undoubtedly at the forefront. Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machining, using multi-axis milling, turning, and grinding machines, allowed for the creation of complex 3D shapes with exceptional accuracy and repeatability. These machines are capable of movements in the micron range, guided by precise digital instructions. However, precision machining is not simply about pushing buttons; it requires skilled machinists who understand material behavior, tooling selection, and the intricacies of the machining process. Furthermore, metrology, the science of measurement, played a critical role. Sophisticated measurement tools, such as Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMMs), laser trackers, and optical comparators, were essential for verifying dimensional accuracy at every stage of manufacturing. These instruments can measure features with micron-level precision, providing feedback for process adjustments and quality control.

Beyond machining, other precision manufacturing techniques might have been employed. Wire Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM), for example, uses electrical discharges to precisely cut intricate shapes in conductive materials, ideal for creating complex features in magnet coils. Precision winding techniques were crucial for fabricating the magnet coils, ensuring uniform wire spacing and layer buildup. This is vital for achieving the desired magnetic field profile and preventing hotspots. Finally, the entire manufacturing environment often needs to be controlled. Cleanrooms and temperature-controlled environments minimize contamination and thermal expansion/contraction effects, which can impact micron-level accuracy. In essence, achieving micron-level precision in the First 4 Magnet manufacturing was a symphony of advanced machinery, skilled craftsmanship, meticulous metrology, and controlled environments, working in concert to push the boundaries of manufacturing capabilities.

## The Intricate Dance of Assembly: Putting the Magnet Together Piece by Piece

With incredibly precise components manufactured, the next monumental challenge was assembly. Imagine assembling a complex jigsaw puzzle, where each piece weighs tons and must be positioned with micron-level accuracy. The assembly of the First 4 Magnet was likely a highly choreographed and intricate process, demanding specialized tooling, meticulous procedures, and a team of experts working in perfect synchronization. How did engineers orchestrate this “intricate dance” of assembly to bring all the meticulously crafted components together?

Specialized lifting and handling equipment was paramount. Heavy-duty cranes, gantry systems, and precision positioning stages were needed to move and orient large, heavy magnet components without causing damage or compromising alignment. These systems often incorporated advanced sensors and control systems to ensure smooth, controlled movements with micron-level precision. Alignment techniques were critical. Optical alignment, laser tracking, and precision jigs and fixtures were employed to ensure that each component was placed in its exact designated position. This required careful calibration and verification throughout the assembly process. Think of it like aligning mirrors in a giant telescope – even minute misalignments can significantly degrade performance.

Joining techniques for magnet components also presented challenges. Welding, brazing, or adhesive bonding might have been used, depending on the materials and structural requirements. However, traditional welding can introduce distortions and stresses, particularly in large structures. Special techniques like electron beam welding or friction stir welding, which minimize heat input, might have been utilized to mitigate these effects. Furthermore, the assembly process likely involved iterative measurements and adjustments. After each component was installed, precise measurements were taken to verify alignment and identify any deviations. Adjustments were then made, often using shims or other fine-tuning mechanisms, to bring the assembly back within tolerance. The entire assembly process was likely meticulously documented and controlled, with checklists, procedures, and quality inspections at every step. It was a testament to the patience, precision, and collaborative spirit of the engineering team, bringing together thousands of individual components into a cohesive, high-performance magnet system.

Here’s a bulleted list highlighting key aspects of the assembly process:

* **Heavy Lifting and Handling:** Utilizing specialized cranes and gantry systems for safe and precise movement of large components.

* **Precision Alignment:** Employing optical alignment, laser trackers, and jigs to achieve micron-level positional accuracy.

* **Controlled Joining Techniques:** Utilizing specialized welding, brazing, or bonding methods to minimize distortion and stress.

* **Iterative Measurement and Adjustment:** Continuously measuring and adjusting alignment throughout the assembly process to maintain tolerances.

* **Cleanroom Environment:** Assembling in a controlled environment to minimize contamination and ensure component cleanliness.

* **Highly Trained Assembly Team:** Requiring a skilled team with expertise in precision mechanics, metrology, and magnet assembly procedures.

* **Detailed Documentation and Procedures:** Following strict protocols and checklists to ensure quality and traceability at each assembly stage.

## Cryogenic Challenges: Maintaining Superconductivity at Extreme Temperatures

Superconductivity, the key to achieving high magnetic fields in the First 4 Magnet, only occurs at extremely low temperatures. This introduces a whole suite of cryogenic engineering challenges. Maintaining these frigid conditions reliably and efficiently is not a trivial task. What were the major cryogenic hurdles engineers had to overcome to keep the superconducting magnets operating at their full potential?

Efficient cooling systems were paramount. Liquid helium, with its incredibly low boiling point of around 4.2 Kelvin (-269 degrees Celsius or -452 degrees Fahrenheit), is often the coolant of choice for superconducting magnets. However, helium is expensive and finite, so minimizing its consumption and preventing boil-off is crucial. Cryogenic systems for the First 4 Magnet likely involved sophisticated cryostats, vacuum-insulated vessels designed to minimize heat transfer from the surroundings. These cryostats incorporate multiple layers of insulation, including vacuum spaces and radiation shields, to block heat radiation and conduction. Cryogenic refrigerators, also known as cryocoolers, were likely integrated into the system to re-condense boiled-off helium and maintain the cryogenic temperature continuously, minimizing helium loss and improving system efficiency.

Thermal management within the magnet itself was also critical. Heat can be generated within the magnet coils due to AC losses (in pulsed magnets) or imperfections. Efficient heat extraction is essential to prevent the superconductor from warming up and losing its superconducting state, a phenomenon known as “quench.” This involved careful design of cooling channels within the magnet coils, ensuring good thermal contact between the superconductor and the coolant. Cryogenic instrumentation and controls were essential for monitoring and regulating the cryogenic system. Precise temperature sensors, level sensors for liquid helium, and control valves were used to maintain stable cryogenic conditions and ensure safe operation. Dealing with cryogenic materials themselves also presents challenges. Materials behave differently at cryogenic temperatures, becoming brittle and exhibiting different thermal contraction rates. Engineers had to carefully select materials that are compatible with cryogenic temperatures, ensuring structural integrity and preventing leaks or failures in the cryogenic system. Overcoming these cryogenic challenges was fundamental to the successful operation and performance of the First 4 Magnet, enabling it to harness the power of superconductivity in a practical and reliable manner.

## Testing and Validation: Ensuring the Magnet Meets Rigorous Performance Standards

After the complex design, manufacturing, and assembly stages, rigorous testing and validation were essential to ensure that the First 4 Magnet met its demanding performance specifications and operated reliably. This phase was not just about flipping a switch and hoping for the best; it involved a systematic series of tests under increasingly challenging conditions. What kind of comprehensive testing regime did engineers implement to validate the performance and reliability of the First 4 Magnet?

Functional testing to verify the basic operational parameters was the starting point. This included energizing the magnet to its design current and measuring the generated magnetic field strength, field uniformity, and field direction. Hall probes and other magnetic field sensors were used to map the magnetic field profile with high precision. Quench testing was crucial for superconducting magnets. A quench is a sudden loss of superconductivity, often triggered by disturbances. Engineers deliberately induced quenches to study the magnet’s quench behavior, verify the effectiveness of quench protection systems, and ensure that the magnet could safely recover from a quench without damage. Thermal performance testing validated the cryogenic system’s efficiency. This involved measuring cool-down times, helium boil-off rates, and temperature stability under various operating conditions. Thermal sensors were strategically placed throughout the magnet to monitor temperature profiles and identify any hotspots.

Mechanical integrity testing assessed the magnet’s structural robustness. This might include pressure testing of cryogenic vessels, vibration testing to simulate operational vibrations, and potentially even fatigue testing to evaluate long-term mechanical reliability under repeated electromagnetic cycling. Safety testing was paramount. Procedures were put in place to test emergency shut-down systems, interlocks, and safety relief valves, ensuring safe operation under both normal and abnormal conditions. Furthermore, performance testing under realistic operating conditions, as close as possible to the intended application environment, was vital. This might involve integrating the magnet with other system components and conducting system-level tests. The entire testing process was likely meticulously documented, with detailed test plans, procedures, and data analysis. The results of these tests provided valuable feedback, allowing engineers to fine-tune magnet performance, identify any remaining issues, and ultimately validate that the First 4 Magnet met its rigorous performance standards and was ready for deployment.

Here’s a numbered list outlining key stages in the testing and validation process:

1. **Functional Testing:** Verifying basic magnet operation, field strength, and field uniformity.

2. **Quench Testing:** Evaluating quench behavior and validating quench protection systems.

3. **Cryogenic Performance Testing:** Assessing cool-down time, helium boil-off rate, and temperature stability.

4. **Mechanical Integrity Testing:** Validating structural robustness under pressure, vibration, and fatigue.

5. **Safety Testing:** Verifying safety systems, interlocks, and emergency procedures.

6. **Performance Testing under Realistic Conditions:** Testing magnet performance integrated within a system, mimicking operational environment.

7. **Data Analysis and Documentation:** Meticulous recording and analysis of test data, detailed documentation of test procedures and results.

8. **Performance Verification Against Specifications:** Comparing test data against design specifications to ensure performance targets are met.

## Innovations Born from Necessity: What New Engineering Solutions Emerged?

The challenges inherent in building the First 4 Magnet were so significant that they inevitably spurred innovation. Necessity is, after all, the mother of invention. Faced with seemingly insurmountable obstacles, engineers were compelled to develop new techniques, refine existing technologies, and push the boundaries of their disciplines. What were some of the truly groundbreaking engineering solutions that emerged directly from the First 4 Magnet project?

New manufacturing techniques were likely developed or significantly improved. Perhaps novel precision winding methods for superconducting coils, advanced joining techniques for dissimilar materials at cryogenic temperatures, or innovative machining processes to achieve unprecedented levels of accuracy. Material science breakthroughs might have been achieved. The project might have driven the development of new superconducting alloys with improved performance, or new structural materials with enhanced strength and cryogenic properties. Cryogenic engineering likely witnessed advancements. Perhaps innovative cryostat designs, more efficient cryocooler technologies, or improved methods for managing heat transfer in cryogenic systems.

Control systems and instrumentation might have seen significant progress. The need for precise control and monitoring of the magnet’s operation, especially in a complex system, could have led to the development of advanced feedback control algorithms, highly sensitive magnetic field sensors, or more robust cryogenic instrumentation. Simulation and modeling tools likely became more sophisticated and accurate. The complexity of the First 4 Magnet probably pushed the limits of existing simulation software, driving the development of more advanced electromagnetic, thermal, and structural analysis tools. Furthermore, the collaborative nature of the project itself, bringing together experts from diverse engineering fields, fostered cross-disciplinary innovation. Engineers from different backgrounds likely learned from each other, sparking new ideas and approaches that wouldn’t have emerged in isolation. The First 4 Magnet project wasn’t just about building a magnet; it was a catalyst for engineering innovation, pushing the entire field forward and leaving a legacy of new knowledge and capabilities.

## Lessons Learned and Future Directions: What’s Next After the First 4?

The journey of building the First 4 Magnet, fraught with challenges and triumphs, has yielded invaluable lessons and opened up exciting avenues for future advancements. Looking back, what key lessons did engineers glean from this complex endeavor, and what are the potential future directions for magnet technology and related engineering fields?

One crucial lesson is the paramount importance of interdisciplinary collaboration. The First 4 Magnet project demonstrably showed that tackling such complex challenges requires bringing together experts from diverse engineering domains – magnet design, material science, manufacturing, cryogenics, control systems, and more. Effective communication, shared goals, and a collaborative spirit are essential for success. Another key takeaway is the power of simulation and virtual prototyping. The project likely heavily relied on computational tools for design, analysis, and optimization, highlighting the increasing role of virtual engineering in tackling complex systems. This approach not only saves time and resources but also allows for exploring a wider design space and identifying potential issues early on.

Precision manufacturing and assembly techniques proved to be critical. The project underscored the need for continuous advancements in manufacturing capabilities, metrology, and automated assembly processes to achieve the stringent tolerances demanded by advanced technologies. Cryogenic engineering remains a vital area for ongoing development. Improving the efficiency, reliability, and cost-effectiveness of cryogenic systems is crucial for wider adoption of superconducting magnet technology. Looking ahead, the lessons from the First 4 Magnet project will likely inform future magnet development for a variety of applications, from scientific research and medical imaging to fusion energy and advanced transportation. Future directions might include:

* **Higher field magnets:** Pushing the boundaries of magnetic field strength through new superconducting materials and innovative magnet designs.

* **Compact and lightweight magnets:** Developing smaller and lighter magnets for portable and mobile applications.

* **Higher temperature superconductors:** Exploring and utilizing high-temperature superconductors to reduce cryogenic cooling requirements and improve system efficiency.

* **”Smart” magnets:** Integrating sensors, actuators, and control systems directly into magnets to enable active field shaping and adaptive operation.

* **Sustainable magnet technologies:** Focusing on energy-efficient designs, materials with lower environmental impact, and closed-loop cryogenic systems.

The First 4 Magnet is not just an endpoint; it’s a stepping stone. It’s a testament to the relentless pursuit of engineering excellence and a foundation upon which even more groundbreaking technologies will be built in the future.

—

## Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the primary application of the First 4 Magnet?

While the specific application might be confidential or varied depending on the context, magnets of this complexity are often used in cutting-edge scientific research, such as particle accelerators for fundamental physics research, fusion energy experiments to confine plasma, advanced medical imaging like MRI or specialized research-grade imaging systems, and potentially in industrial applications requiring extremely strong and precisely controlled magnetic fields.

How long did it take to design and build the First 4 Magnet?

Projects of this complexity typically span several years, from initial conceptual design to final testing and validation. The design phase alone could take one to two years, followed by manufacturing and assembly which might take several more years, depending on the scale and complexity, and finally, a significant period for testing and commissioning. A timeline of 5-10 years for development and construction wouldn’t be unusual for a truly groundbreaking magnet system.

What was the size and weight of the First 4 Magnet?

Without specific details, it’s difficult to give exact figures. However, complex magnets like this can range in size from a few cubic meters to much larger, depending on the application. Weights can range from several tons to tens or even hundreds of tons for very large systems. The size and weight are dictated by the required magnetic field volume, field strength, and the materials used in construction.

Were there any unexpected setbacks or challenges during the project?

Absolutely. Large-scale, cutting-edge engineering projects invariably encounter unexpected challenges. These could range from material supply chain issues to unforeseen manufacturing difficulties, unexpected test results requiring design modifications, or integration problems with other system components. Engineering is, in many ways, about anticipating and overcoming these challenges. Resilience, adaptability, and problem-solving expertise are crucial for navigating such setbacks and ultimately achieving project success.

How many engineers were involved in the First 4 Magnet project?

Projects like this are highly collaborative and involve teams of engineers with diverse specializations. The team size could easily range from dozens to potentially hundreds of engineers at various stages of the project, including magnet designers, material scientists, manufacturing engineers, cryogenic engineers, electrical engineers, control system engineers, test engineers, project managers, and support staff. It’s a truly collective effort requiring coordination and expertise across multiple disciplines.

Is the technology used in the First 4 Magnet applicable to other fields?

Yes, definitely. The technologies and innovations developed for complex magnets often have broad applicability. Advancements in superconducting materials, cryogenic systems, precision manufacturing, and magnetic field control can benefit numerous other fields, including medical technology, energy generation and storage, transportation, advanced materials processing, and various other scientific and industrial sectors. Innovation in one area often has ripple effects, driving progress in seemingly unrelated fields.

—

## Conclusion: Key Takeaways

* **Engineering Ingenuity Conquers Complexity:** The First 4 Magnet stands as a powerful example of engineers overcoming immense challenges through innovation and determination.

* **Interdisciplinary Collaboration is Crucial:** Success hinged on bringing together diverse expertise, highlighting the power of teamwork in tackling complex problems.

* **Precision Manufacturing at the Micron Level:** The project pushed the boundaries of manufacturing and assembly, achieving incredible accuracy.

* **Cryogenic Mastery for Superconductivity:** Maintaining extreme temperatures reliably was essential and showcased advancements in cryogenic engineering.

* **Innovation Driven by Necessity:** The project spurred new engineering solutions and pushed the boundaries of multiple technological fields.

* **Lessons Learned Pave the Way for the Future:** The experiences and innovations from the First 4 Magnet will shape future advancements in magnet technology and beyond.

Thank you for joining me on this exploration of the First 4 Magnet project. I hope this glimpse into the world of engineering innovation has been both informative and inspiring. Remember, behind every technological marvel, there’s a story of dedicated engineers overcoming challenges and pushing the limits of what’s possible. Keep exploring, keep innovating, and never underestimate the power of human ingenuity!